Principle 3 Recovery of ecosystem attributes is facilitated by identifying clear targets, goals and objectives

A restoration project will have greater transparency, manageability and improved chances of success if the restoration targets and goals are clearly defined and translated into measurable objectives. These can then be used to monitor progress over time, applying adaptive management approaches (Box 3).

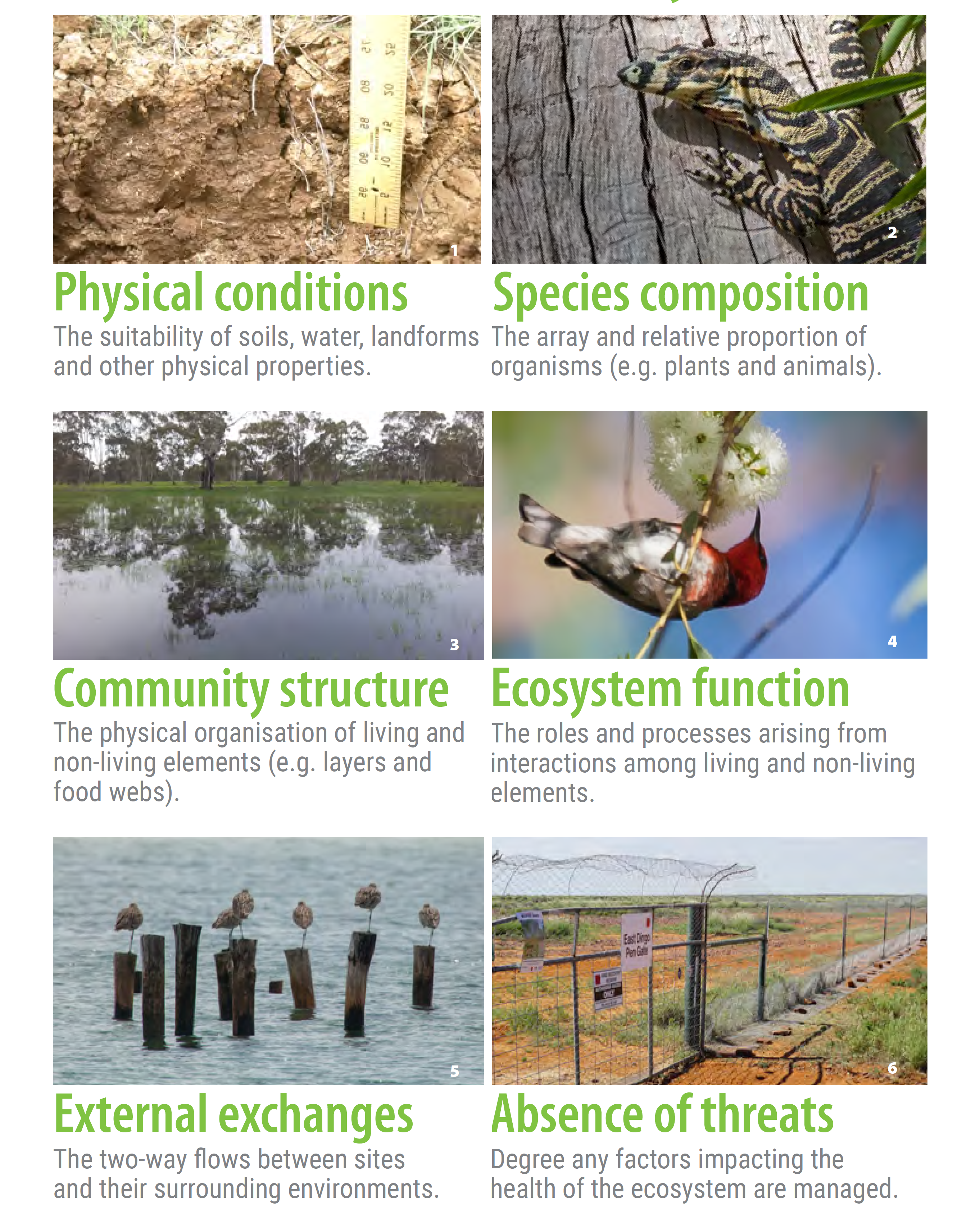

Ecological references identify the particular terrestrial or aquatic ecosystem that informs the target of the restoration project. This involves describing the specific compositional, structural and functional ecosystem attributes requiring reinstatement before the desired outcome (the restored or substantially recovered state) can be said to have been achieved.. The Standards list the ecosystem attributes (rationalised from those of the SER Primer) as: absence of threats, physical conditions, species composition, community structure, ecosystem function, and external exchanges (Figure 4). These attributes in combination can then be used to derive a five-star rating system (see Principle 4) that enable practitioners, regulators and industry to track restoration progress over time and between sites.

That is, a restored state is considered to have been achieved when the ecosystem's attributes are on a secure trajectory approximating those in the ecological reference without further repair-phase interventions being needed other than ongoing protection and maintenance. At that stage the ecosystem under recovery would be considered 'self-organising' and increasingly resilient to natural disturbances.

Each ecosystem attribute will comprise a range of more detailed component properties, that in turn inform goals and objectives needed to

achieve the target. These component properties have different expressions in different biomes and different sites, which will mean that each

project will have site-specific targets, goals and objectives aligned with specific (measurable) attributes (Box 4). Specific indicators are selected to

help evaluate whether these targets, goals and objectives are being met as a result of the interventions (Boxes 3 and 4, Appendix 4).

Six key attributes of a reference ecosystem

Figure 4 Restoration goal-setting and monitoring needs to be carried out for each of the six attributes. (Figure: Little Gecko Media, Photos: 10 Ray Thompson, 12 Mark Bachman, 15 Arid Recovery, 2, 4, 5 Virginia Bear.)

Box 3 Restoration monitoring and adaptive management

Monitoring the responses of an ecosystem to restoration actions is essential to:

- identify whether the actions are working as expected or need to be modified (i.e. adaptive management);

- provide evidence to stakeholders that specific goals are being achieved (Box 4); and,

- answer specific questions - e.g. to evaluate particular treatments or what organisms or processes are returning to the ecosystem.

Adaptive management is a form of 'trial and error'. Using the best available knowledge, skills and technology, an action is implemented and records are made of success, failures and potential for improvement. These learnings then form the basis of the next round of 'improvements'. An adaptive management can and should be a standard approach for any ecological restoration project irrespective of how well-funded that project may be.

- The most direct and critical form of monitoring for adaptive management is routinely inspecting the site to identify whether restoration actions are working or need to be modified. Such monitoring is undertaken by the project supervisor to identify any need for a rapid response and to ensure appropriate treatments can be scheduled before problems become entrenched. Additional inspections are also needed after episodic events such as storms, floods, fire, severe frost and droughts.

- The minimum formal monitoring required for adaptive management - and to provide evidence to stakeholders and regulators that goals are

being achieved - is to maintain a photo monitoring record of the site being treated, using a fixed photopoint. All monitoring, - even time series

photos - needs to have evidence of 'before' condition. This is because, once the whole site is treated, a photo may be the only evidence that change

has occurred. Photo monitoring at control (untreated) sites is also recommended, where possible. For larger sites, aerial photography may also

provide useful before and after imagery.

Well-funded projects (or projects under regulatory controls e.g. mine site restoration) are expected to undertake formal comprehensive monitoring for adaptive management and reporting to stakeholders. This usually involves professionals or skilled advisors and is based on a monitoring plan that identifies, among other things, monitoring design, timeframes, who is responsible, the planned analysis, and frameworks for response and communication to regulators, funding bodies or other stakeholders.

The monitoring design of projects may involve development or adaptation of a condition assessment system or formal sampling system to track the progress of specific indicators, whether they be abiotic or biotic. In some cases individual species or groups of species can function as surrogates for suitable abiotic conditions. For soil microorganisms, one or more quantitative determinants are used consistently throughout the life of the restoration project to ensure that the functional diversity of the microbial communities is restored in soils. Formal sampling of plant and animal populations can involve a range of faunal trapping and tracking methods or vegetation sampling using randomly located quadrats or transects. Design of such monitoring schemes should occur at the planning stage of the project to ensure that the project's goals, objectives and their selected indicators are measurable and that the monitoring aligns with these goals. Care should be taken to ensure that the sampling commences prior to the commencement of restoration treatments, and where possible, control sites should be included in the design. If the necessary skills are not available in-house, advice should be sought from relevant professionals with experience in designing site-appropriate monitoring, documenting and storing data, and carrying out appropriate analysis. - Monitoring can be used to answer questions (hypotheses) about new treatments or the return of organisms or processes-but only if the data collected are well matched to the particular question and an appropriate experimental design is employed. A restoration project that is comparing or trialling techniques needs to observe the conventions of replication and include untreated controls in order to interpret the results with any certainty. Rigorous recording is also needed of specific restoration treatments and any other conditions that might affect the results. A standard practice in such a situation would be for the practitioner to partner with an ecologist or relevant scientist to ensure the project receives the appropriate level of advice and assistance. Where new treatments are being considered or where the nature of the site is uncertain, treatments are first trialled in smaller areas prior to application over larger areas.

Box 4 Targets, goals and objectives - what terms should we use?

It is useful to have a hierarchy of terms such as 'target', 'goals' and 'objectives', to better organize planning so that proposed inputs are well matched to the desired ultimate outcomes.

While there is no universally accepted terminology and many groups will prefer to use their traditional terms, the Standards broadly adopt the terminology of the Open Standards for the Practice of Conservation Open Standards for the Practice of Conservation.

It helps to think of objectives needing to be S.M.A.R.T.( i.e. specific, measurable, achievable, reasonable and time-bound). They should be directly connected to key attributes of the target ecosystem. This is achieved by the use of specific indicators.

Hypothetical example:

- Target. Where the aim is full recovery, the target of a project should align with the specific reference community to which the restoration project is being directed—e.g. ‘Box-Ironbark Forest’—and will include a description of the ecosystem attributes. In projects where substantial (but less than full) recovery is the aim, the target should reflect the reference ecosystem even if it cannot fully align with the reference

- Goal/s. The goal or goals provide a finer level of focus in the planning hierarchy compared to the target. They describe the status of the target

that you are aiming to achieve and, broadly, how it will be achieved. For example, goals in this hypothetical project may be to achieve:

- An intact and recovering composition, structure and function of remnants A and B within five years within 5 years, including visitation by at least two declining woodland bird species;

- 20 ha of revegetated linkages between the remnants within 10 years; and,

- 100% support of all stakeholders and neighbours within five years.

- Objectives. These are the changes and intermediate outcomes needed to attain the goal/s. For example preliminary objectives may be to

achieve:

- Less than 1% cover of exotic plant species and recruitment of at least two obligate seeding native shrub species in the remnants within 2 years; and,

- ii A density of 300 stems /ha of native trees and shrubs, at least three native herb species / 10 m2 and a coarse woody debris load of 10 m3/ha in the reconstructed linkages within three years.

- iii Cessation of all livestock encroachment and weed dumping within one year and formation of a ‘friends’ group representing neighbours within 3 years.

(For other examples of some detailed indicators, see Appendix 4)